The 511 on Remuneration

With conduct and culture at financial institutions remaining at the forefront of remediation work and regulatory involvement following the Royal Commission, it should come as no surprise that APRA is now seeking to strengthen requirements on remuneration.

Back in November 2020, APRA released a revised draft remuneration standard and second consultation. Consultation on the revised draft APRA Cross Industry Prudential Standard CPS 511 Remuneration (CPS 511) recently closed on 12 February 2021 and the final standard is expected to be released during the second quarter of 2021.

The key revisions for Significant Financial Institutions (SFIs) include:

· Replacing the 50 per cent cap on financial measures for variable remuneration with a requirement that material weight be assigned to non-financial measures, combined with a risk and conduct modifier that can potentially reduce variable remuneration to zero.

· A reduction in the minimum deferral periods for variable remuneration from seven to six years for CEOs, from six to five years for senior managers and from six to four years for highly paid material risk takers.

· Extension of the effective date of the standard out to 1 January 2023, from the original planned date of 1 July 2021.

The remuneration requirements for smaller entities have also been streamlined, and will not be subject to some elements impacting variable remunerations.

While many of the elements of draft CPS 511 should already be familiar to entities from both the existing remuneration requirements of CPS/SPS 510 Governance and the Banking Executive Accountability Regime (BEAR) legislation, APRA is attempting to move remuneration practices into the future with the inclusion of some new initiatives. These initiatives are essentially aimed at encouraging organisations to improve the design of their incentive schemes in order to better support the long-term objectives of the company.

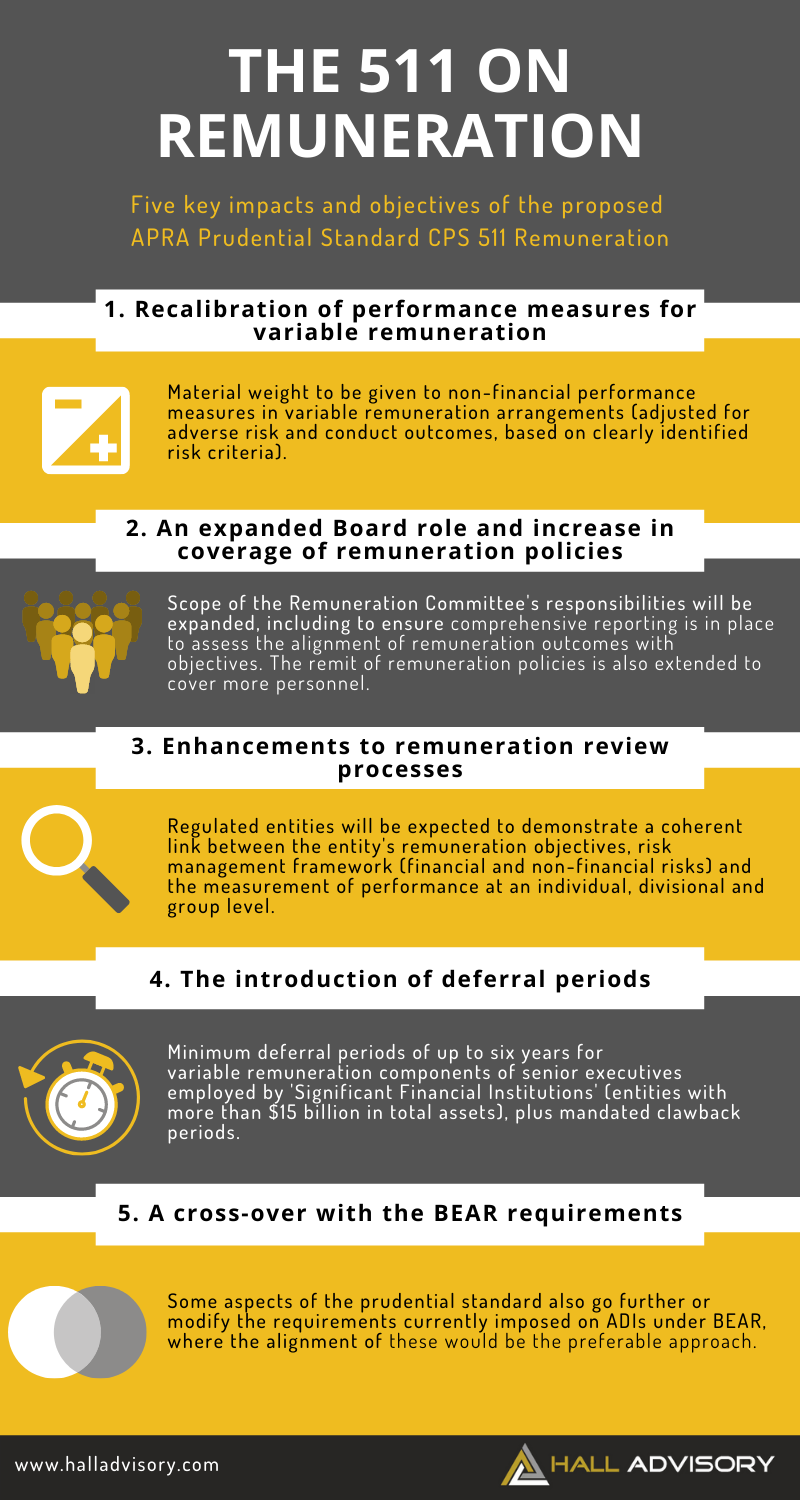

Five key impacts and objectives of the proposed prudential standard are explored below.

1) Recalibration of performance measures for variable remuneration

APRA’s view is that financial targets have had too prominent a place in executive remuneration in some sectors of the financial services industry and that there needs to be much better alignment and balance between financial targets, customer-centric measures and remuneration arrangements that reflect skill and expertise.

As a result, APRA has proposed that a material weight is given to non-financial performance measures in variable remuneration arrangements; and be adjusted for adverse risk and conduct outcomes, based on clearly identified risk criteria. (This replaces the previously proposed 50% cap on the use of financial performance metrics).

While APRA is not proposing to cap the amount of variable remuneration or fixed salary amounts of employees or executives of regulated entities in absolute terms, the scope of CPS 511 is far reaching. It is proposed that all variable remuneration arrangements across the group be prudentially regulated regardless of the seniority of the employee.

All variable remuneration arrangements across the regulated group would have to satisfy design criteria and be subjected to an overarching obligation to take appropriate steps to assess and mitigate conflicts in their design (such as metrics focused on volumes or sales).

What is included as a financial performance measure?

Essentially any financial measure that is not risk-adjusted and that relates to financial performance, such as share price, total shareholder return, return on equity (RoE), profit, revenue, sales and other volume-based measures. Risk-adjusted capital adequacy or risk-adjusted cost of funding are excluded.

What non-financial measures should organisations be considering?

APRA has made note of five categories that are being used internationally to capture non-financial metrics. These categories are:

1. Effectiveness and operation of control and compliance (conduct and risk).

2. Customer outcomes (customer satisfaction, customer loyalty and service quality/complaints).

3. Market integrity objectives (innovation and sustainability).

4. Reputation (brand, reputation and net trust score).

5. Alignment with strategy or values (cross-bank collaboration, culture metrics, diversity, employee engagement, entity specific strategic priorities, and leadership and teamwork).

Organisations will need to consider using an appropriate mix of the above measures to compliment the financial measures.

Mandating a requirement for a material weighting of non-financial performance measures has drawn criticism from stakeholders concerned that non-financial measures can be manipulated, may not be as reliable as financial measures and may be seen as rewarding business as usual responsibilities. APRA has responded by noting that these issues should be managed via remuneration design and by limiting the weighting of non-financial measures which have adverse financial outcomes.

Others have raised concerns that the use of an overly prescriptive approach may discourage the consideration and development of other tools like gateways and modifiers, and could undermine the broader goal of encouraging Boards to use more judgement and discretion. APRA has responded by reverting to a principles-based approach, allowing flexibility.

APRA is also now grappling with how to deal with other concerns and potential unintended consequences like organisations shifting away from a wider use of variable remuneration to higher levels of fixed remuneration, which has already been observed at several organisations.

2) An expanded Board role and increase in coverage of remuneration policies

The scope of the Remuneration Committee's responsibilities will be expanded under the new Prudential Standard. This includes a requirement to ensure that comprehensive reporting is in place to allow assessment of whether the remuneration outcomes of all remuneration arrangements align with the entity’s remuneration objectives. The Committee will also need to oversight findings from annual remuneration framework reviews and triennial independent reviews to ensure that they are addressed and implemented.

Requirements around making assessments and recommendations to the Board on both remuneration arrangements and variable remuneration outcomes will be extended to a broader category of employees who fall within a 'Special Role'. The special role category will cover senior managers, those considered a 'highly paid material risk-taker', and risk and financial control personnel. Within this, a formal process must be implemented for the Remuneration Committee to consult with the Risk Committee and the CRO to ensure that risk outcomes are reflected in the remuneration outcomes for employees in these special role categories. In addition, it is expected that the Board will retain responsibility for the overall remuneration framework and be directly involved in overseeing the remuneration arrangements and approval of the remuneration outcomes of persons falling within the special role category.

The remit of remuneration policies will also need to be extended to cover more personnel. A specific requirement has been added for the remuneration policy to provide a description of the structure and terms of remuneration arrangements that apply across all employees of the relevant group and certain service contractors (not just senior executives and other roles as specified under current prudential standards).

Alongside this broadened scope, the Board is essentially expected to apply a greater level of judgement and discretion in the application of variable remuneration outcomes. How much the Board should be relied on to provide this judgement is open for debate, with some saying that if they have historically failed to apply this discretion, there is no reason to be confident that they will provide the needed improvement in the future. There is also a limit to the oversight that directors can provide in the process, noting that for the most part they fulfil non-executive roles.

3) Enhancements to remuneration review processes

Further development of infrastructure to support remuneration review processes and information flow to substantiate variable remuneration outcomes will be required to satisfy CPS 511 requirements. Regulated entities will be expected to demonstrate a coherent link between the entity's remuneration objectives, risk management framework (financial and non-financial risks) and the measurement of performance at an individual, divisional and group level. That measurement will also need to be reflected in variable remuneration outcomes across the organisation.

If remuneration objectives are not met, or there is a significant unexpected event which impacts a range of measures, variable remuneration outcomes must be adjusted downwards (for all employees, not just those in senior executive roles), whether by way of in-period adjustments, malus, clawback or overriding discretion. Specific criteria for the application of malus (an adjustment to reduce the value of all or part of deferred variable remuneration before it has vested) will need to be implemented that covers a significant downturn in financial performance, evidence of misconduct or negligence, failure of financial or non-financial risk management, failure to meet code of conduct or significant adverse outcomes for customers.

4) The introduction of deferral periods

APRA has proposed minimum deferral periods of up to six years for variable remuneration components of senior executives employed by SFIs, as well as mandated clawback periods.

The proposed definition of a SFI captures entities with more than $15 billion in total assets. The following will apply for SFIs in respect of any person with deferred variable remuneration of >AUD$50,000 in a financial year:

- CEO remuneration: 60% of total variable remuneration shall be subject to a deferral period of 6 years (with pro-rata vesting from year 4).

- Senior managers and employees falling within a Special Role: 40% of total variable remuneration shall be subject to deferral period of 5 years (with pro-rata vesting from year 4).

- ‘Highly paid material risk taker’: 40% of total variable remuneration shall be subject to deferral period of 4 years (with pro-rata vesting from year 2).

- Clawback: Variable remuneration must also be subject to mandatory clawback for a period of at least 2 years from vesting (or, where a person is under investigation, variable remuneration must not vest until the investigation is closed).

These deferral periods are intended to provide more 'skin-in-the-game' through better alignment to the time horizon of risk and performance outcomes. Much of the conversation so far has been around the length of the deferral period, with differing views on what is appropriate and how this may be impacted across different roles within the organisation and across different industries.

5) A cross-over with the BEAR requirements

Malus and deferral arrangements set under BEAR will likely require revision (subject to any changes stemming from the consultation process). Accountability statements and maps may require updating if responsibilities change as a result of implementing the new prudential standard.

Some aspects of the prudential standard also go further or modify the requirements currently imposed on ADIs under BEAR (deferral requirements and criteria for malus are two specific areas identified by APRA), where alignment of these would be the preferable approach.

Next steps

Noting the interest that this topic has generated and the significant amount of feedback that was provided to APRA during the initial consultation period, we can expect to see further communications and considerations by APRA before the final version of CPS 511 is decided.

Comments